News and Stories

Every community has a story

Rural advocates, thought leaders, students and community builders are leading our region toward a stronger, more inclusive future for children and their families. Read their stories here. Looking for Foundation news? See our latest press releases.

OR

Our kids deserve safe, hopeful childhoods

SelectBooks offers two-book bundle during Child Abuse Prevention Month. These books, “My Body Belongs to Me” and the accompanying parent’s guide, address boundaries, safety and consent.

Voices on Oregon’s housing crisis

The first research brief from the Oregon Voices survey highlights the housing issue in the words of the people who are living through it.

Oregon artist stirs conversation

For visual artist Lisa Jarrett, art is about much more than making objects. It is about exploring identity, forging connections, creating community and providing opportunities.

Webinar: Rural community building as a philosophy, not an initiative

Join us on February 2, 2024 from 12-1:00PST for a Q&A with the authors of a recent article on rural community building.

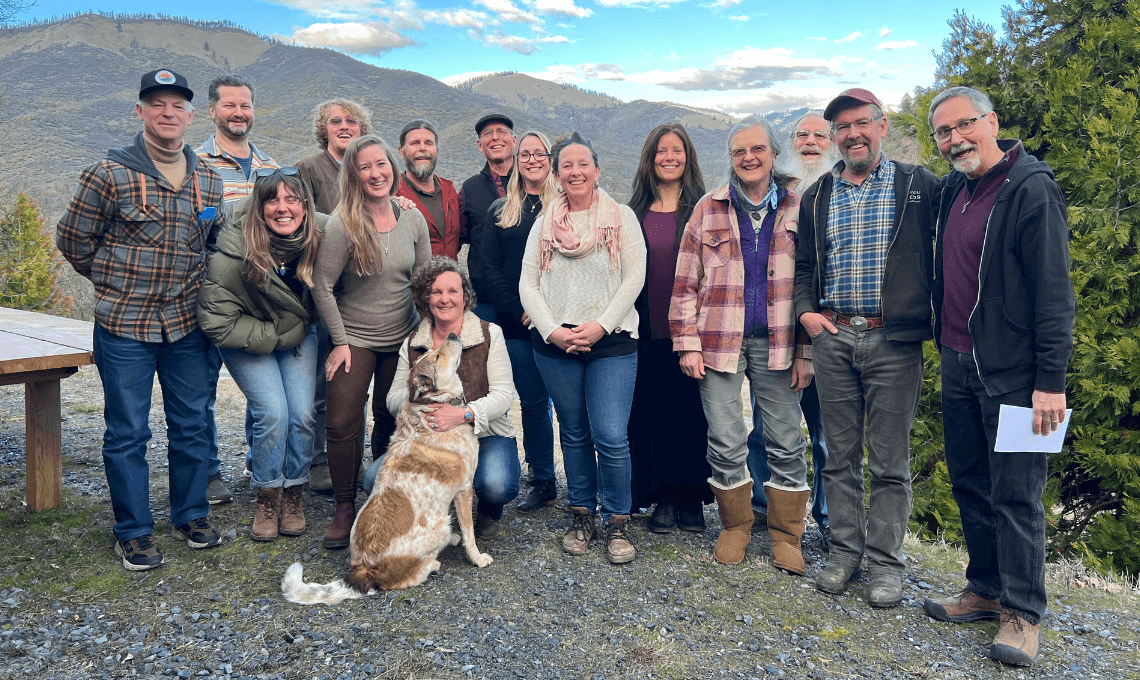

Reflections on community building in the Applegate Valley

Prior to forming A Greater Applegate, the area’s leading community building organization, the complicated overlap of geography and government agencies challenged residents’ sense of a shared identity and made advocating for their needs difficult.

Meet our newest field coordinators

Field coordinators are at the heart of The Ford Family Foundation’s Community Building Approach. These locally based team members serve as resources and agents for change in their community, whether that community is a rural region or a specific population.

Heritage and community

Ford Scholar Will Miller connected with his history to create his future and now works at NAYA, the Native American Youth and Family Center.

Yoncalla Early Works is “kind of a big deal”

Over the course of ten years, Yoncalla School District leaders and community members, especially parents of young children, have walked side-by-side reinventing the elementary school’s approach to family and child support.

Celebrating our leadership transition

This week we celebrated the retirement of Anne Kubisch and welcomed Kara Carlisle as the third president and CEO of The Ford Family Foundation.

The health of a community

Analicia Nicholson just started the biggest job she’s ever had: She’s the new superintendent of the Douglas Educational Service District. On a recent Zoom call, she shared her hopes, fears and all the unknowns of the position.

Subscribe to Foundation

News and Stories