Sifuentez brings to life the untold stories of Oregonians essential to the state’s past, present and future

In 2016, Mario Jimenez Sifuentez published Of Forests and Fields: Mexican Labor in the Pacific Northwest. His book shares the story of Mexican immigrants who, out of view of most Oregonians, became the foundation of our agriculture economy in both the irrigated fields and managed forests of Oregon. Sifuentez brings to life the untold stories of Oregonians essential to our state’s past, present and future. He begins with the federal Bracero program that imported Mexican laborers to rescue American crops during World War II, explores the lasting cultural impacts that migrant labor brought to the state and ends with the struggle to secure rights for these people that built community and added wealth to the nation.

Mario, can you start us off with who you are and what your relationship is to this story?

I grew up in Ontario, Oregon, working in the onion fields with my family. My parents were Mexican farmworkers that had been coming to the area for a long, long time, starting with my grandfather who migrated there for seasonal farmwork.

Well, now you’re a published author and a college professor with a Ph.D. What was your path to education?

It all starts in the fields. I was a terrible farmworker, and my mother used to say, el lápiz pesa menos que la pala: the pencil weighs less than the shovel. It was her way of saying, if you don’t like it then you need to study.

Growing up, I didn’t want to know anything about farming. I just wanted to get away from that life as much as possible. And now I’ve come full circle as an agricultural historian.

My aunts and uncles and cousins that still work in the field, love being outside. The work itself is respectable, dignified work – it just doesn’t pay well. It’s the exploitation that you don’t like.

So even though I didn’t want to be in that life, I really respected the people in it. They were the hardest working people I knew. And when I got to college, I took all these classes in ethnic studies, and learned about Cesar Chavez and read stories about Texas and California. And I kept asking – what about Oregon? Where are the books about Oregon?

While I was an undergraduate at University of Oregon I was deeply involved in organizing work and I thought that’s what I was going to do. And then during a meeting with my adviser, he said, “You’re always asking about these books on Oregon. Why don’t you write it?”

And that was an important moment for me. We have this reverence for books and have a hard time understanding where they come from. He told me about his process for writing a book and said, “You know the place and the people and you have the connections. If you’re not going to write it, who is?”

That struck me deeply. It kind of all came together at that moment and I realized this is something I could do. This is for me. And I agreed to start a master’s program, and eventually went to Brown with him for a Ph.D.

And I was ill-prepared for graduate school. It was so beyond my scope – a totally different world. I grew up in a small town in Eastern Oregon and yeah, I had heard of Harvard but I couldn’t have told you where it was. I wouldn’t have made it through without this being a deeply personal project.

It was almost an accident, getting there, but it was all driven by a question about what my place in the world was. And it quickly went from a personal existential crisis to a political one: How did we end up here?

In your book, you use oral histories – the personal recollections of people that lived through it – to tell your story. How did you arrive at oral history as a research method, and what did it do for your storytelling?

The first roadblock I ran into while doing research as a traditional historian was that all the sources I found – reports, statistics, stories – were all what white people thought about Mexicans. And that’s not what I wanted to contribute to.

Dance halls, radio stations, business, community centers — thriving, viable communities were created as a result of the Bracero program (1942)

Eventually, I found a Smithsonian photo collection on the Bracero program and they wanted to get the stories of the people in the photographs. We got a grant to track them down, and I started doing oral histories in farm towns across the country. As a native Oregonian, I could relate to people and fill in details. I was able to say, “Oh, you worked in sugar beets? I worked in sugar beets,” and I could identify the places they were talking about but couldn’t remember.

And that’s how I found the story of my uncle dying, a man I had never met. I found an old newspaper article about him dying in a farming accident. And when I confronted my family about it, they were like, “Oh. Yeah.” And it made me realize that these stories are right underneath our noses. And for a lot of reasons, trauma or whatever, people don’t want to talk about them. And it becomes crucial for us to get people to talk about them. We interviewed over 800 people. Without fail, the old men would say, “I don’t know why you’re talking to me, I didn’t do anything important.”

And you have to understand, these people changed the course of this nation. Everywhere the Braceros were, Mexican communities were created. Before the Bracero program, there weren’t any Mexicans in Oregon. Thriving, viable communities with dance halls, radio stations, businesses and neighborhoods all happened because of the program.

We would always send a copy of the oral histories we recorded to the families. And without fail, the kids of the Braceros would be like, “Oh, I had no idea. I had no idea that they went through this.”

Your book centers around the Bracero program, in which the federal government imported Mexican labor for the agriculture industry in the 1940s. Can you give us a rundown on the program?

The Bracero program was a bilateral agreement between Mexico and the United States that was supposed to be a wartime effort to alleviate labor shortages during World War II. The war created a mass mobilization of primarily white American men into the military that left rural communities with what was presumably a labor shortage, which certainly wasn’t the case after the war when the program continued until 1964. After the war, the growers that had used the Bracero program had become accustomed to an easily governable – easily manipulated – workforce that became a staple of agricultural labor.

Up until this point, the literature of the Bracero program discussed the evils and the exploitation of the program – and I by no means want to downplay the horrific exploitation that took place because of the program – but I also wanted to write a book about people, and how their lives were changed by the program.

One aspect of oppression is that people find ways to thrive. We find ways to enjoy ourselves – to laugh, to have dignity. And that gets lost when you write about exploitation. I wanted to humanize the men that went through that program.

You also tell the stories of Bracero program laborers that ended up working for the Forest Service, fighting wildfire and doing other forestry work. You mention how the Forest Service became the largest employer of undocumented immigrants – by employing forestry contractors that hired mostly immigrant labor.

One of the myths about undocumented immigrants is that they are working illegally and not paying taxes. That’s not true. They are being employed by the federal government and are out doing work on federal lands – and paying federal taxes.

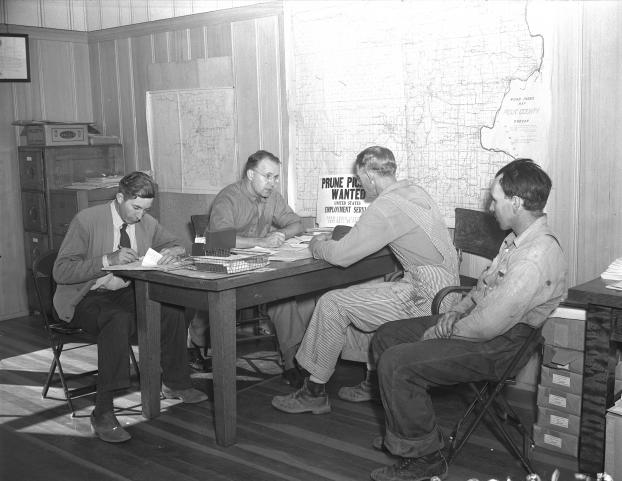

Contracting for labor: Bryant Williams, farm labor assistant, and Preston Daughton, USES representative, arrange with S.E. Starr and K.A. Bursell for Mexican workers.

Growing up in Oregon I had cousins that were firefighters, but there’s a much longer history that didn’t occur to me. In Oregon, we often see forests as a naturally occurring thing, but in reality they are treated like a crop. Forestry is industrial agriculture. And when you have a crop, someone has to be out there managing it. Trees need to be sprayed, they need to be thinned, they need to be planted, they need to be harvested. And it’s Mexican immigrant labor that’s doing a lot of that.

The irrigation of Eastern Oregon and the timber boom of the 1960s and ‘70s was not possible without Mexican labor. And people don’t realize that.

In the book you paint a picture of a rich, multicultural eastern Oregon where Mexican culture found a place to flourish in Japanese community centers, which hosted dances and weddings and baseball leagues. Can you explain how that came to be?

During Japanese-American internment in World War II, Ontario became a city where Japanese could live freely during the war. And there are all these instances of the Japanese helping the Mexican community establish itself in Eastern Oregon.

I grew up with the sons of Japanese farmers, and there was a lot of racial tension. When I started researching, I had a preconception of terrible Japanese bosses. But when I talked to the man that contracted my parents as laborers, he said he was only able to be a contractor because of Japanese growers. And the more I talked to Japanese growers, I realized that it was only because of them that Mexicans and Tejanos, legal migrant workers from Texas, were able to stay in Ontario.

Japanese growers found a niche growing onions, and opened up packing sheds and were able to employ migrant workers in the winter. This gave them the opportunity to stay – which became really important. And in that time, white people wouldn’t rent to Mexicans, but the Japanese would. And so Japanese and Mexican neighborhoods came up. In Ontario, the Japanese dance hall became a cultural hub for Mexicans – it hosted quinceañeras, weddings and a baseball league.

At the time, with the de facto segregation, Mexicans were not allowed to occupy white spaces.

What was it like when you were growing up there?

As the child of a farmworker, no one would let you forget that you were the child of a farmworker. We faced a lot of nasty stuff, but there were always people who were supportive of our community. I was made acutely aware of who I was very early in life – but that doesn’t diminish the history of the town having progressive people doing very impactful things.

The history of the Bracero program, and of immigrant labor, isn’t well known in Oregon. Why do you think that is?

To a certain extent, labor is always invisible. Whether it’s housecleaning, child raising or whatever, there’s labor that’s happening that’s invisible. And a lot of it is physically invisible – it’s happening out in the fields, or way out in the forests where people don’t see it. You have no idea the amount of labor that goes into providing the lifestyle that you live. Part of what I was trying to do is make that labor literally and figuratively visible.

Throughout the book, you center on the theme that labor creates wealth enjoyed by everyone in the nation. You mention the saying, con o sin papelas, tenemos derechos porque hacemos la riqueza– with or without documents, we have rights because we create wealth. Why do you feel that is important?

It decenters the nation state. It highlights the fact that this question of citizenship is irrelevant – if you live and labor in a community, you belong to that community.

A lot of academics want to write the definitive text on X, Y and Z. For me, it was, I’m gonna write the first text. My biggest ambition with the book is that it would unleash a storm of other people from places like Medford, Nyssa and Hood River to tell their stories – and it has. There’s a whole generation behind me whose books will be coming out in the next few years, and they’re citing my work.

They’re asking the same question I had when I was eighteen: How did we end up here?