News and Stories

Every community has a story

Rural advocates, thought leaders, students and community builders are leading our region toward a stronger, more inclusive future for children and their families. Read their stories here. Looking for Foundation news? See our latest press releases.

OR

Action needed to support Oregon’s transfer students

Creating easy-to-navigate transfer pathways from two- to four-year colleges and universities is not an impossible task. We need bold action to create the transfer system our students deserve.

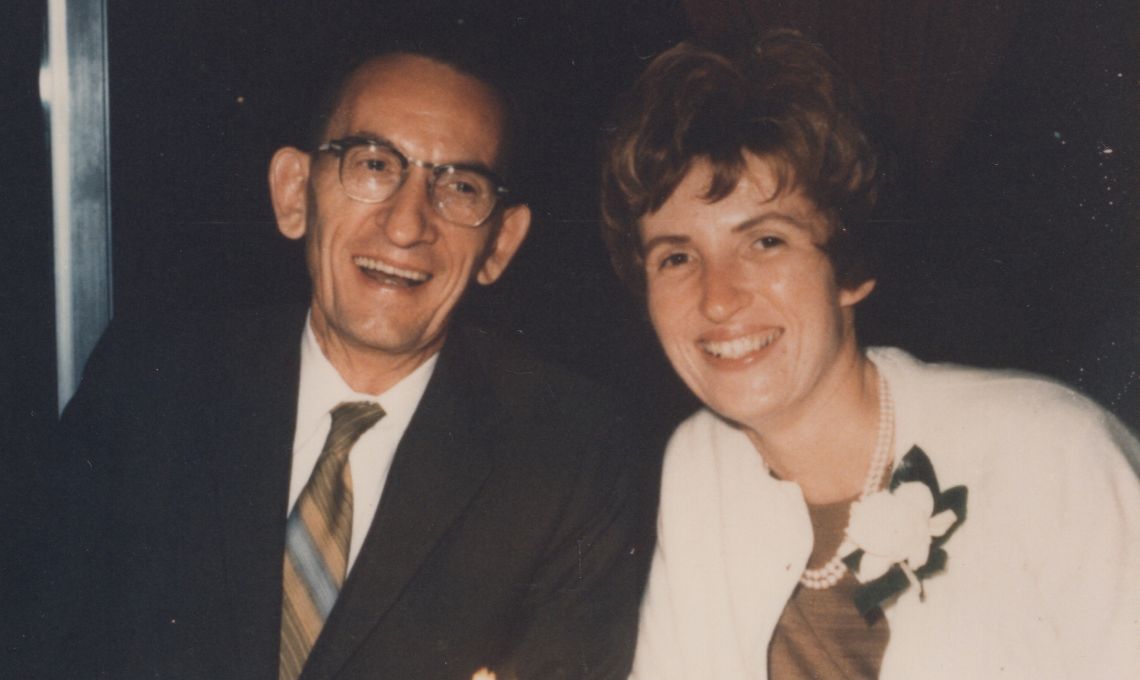

A tribute to Carmen Ford Phillips

A tribute to Carmen Ford Phillips, the only daughter of Kenneth Ford and Hallie Ford and former family representative on The Ford Family Foundation Board of Directors.

Communications to build community

Jennifer Lindsey has lived and worked in many places, but when she moved back to Oregon a decade ago, it felt like a homecoming. The new communications director for the Foundation, Jennifer is responsible for all internal and external communication efforts.

Child welfare and the power of parent voice

Parents with lived experience of the child welfare system in Douglas County are now working with ODHS to improve outcomes for children and families.

Supporting families, preventing harm

Last month, we celebrated Child Abuse Prevention Month — a powerful reminder of our shared responsibility to keep kids safe, especially in rural communities across Oregon where resources can be limited and families face unique challenges.

The backbone of rural Oregon’s economy

Launched in 2021, GRO currently supports four rural communities to build a network — a community ecosystem — that wraps around in support of local entrepreneurs. Find inspiration for ways to support small business in your community from these standout examples.

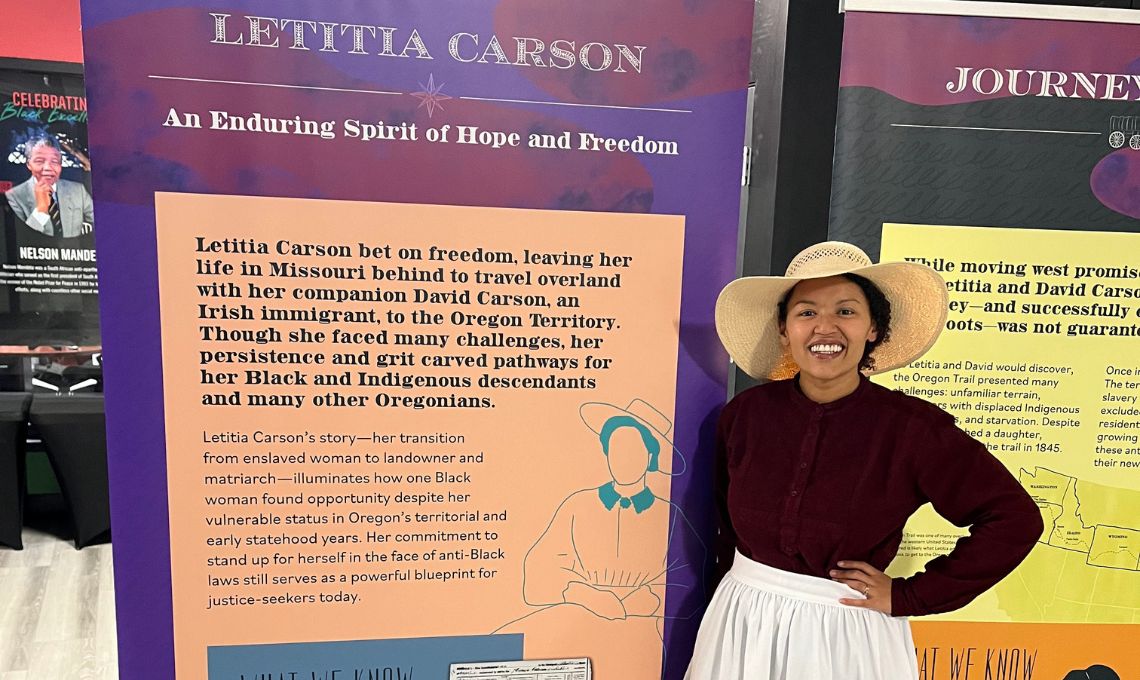

Telling her story

There is little chance now that Black settler Letitia Carson’s story will recede from memory. Her story is one of resilience, persistence and triumph. One of Carson’s most memorable claims to history is as an early Black homesteader in two Oregon locations.

Exploring trends on boys and men

Richard Reeves, author of “Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male Is Struggling, Why It Matters, and What to Do About It”, talked about declining male enrollment and other complex and concerning trends before a packed auditorium at Umpqua Community College.

Alumni build bridges to higher education

The Alumni Ambassador program has grown in recent years, as ambassadors are carefully chosen to represent priority demographics. Their expertise helps surmount language, geographic, gender and other barriers as they seek out and engage with potential scholars.

A passion for education for seven generations

We’re thrilled to introduce Christi Boyter as the new Alumni Engagement Coordinator at The Ford Family Foundation! With a wealth of experience in education, Christi is perfectly suited for this role.

Subscribe to Foundation

News and Stories